Was Metrical Singing Part of The Last Supper?

The ancient Passover rituals differed in various ways from the practices we observe today. Insights from Hebrew writings following the second temple period shed light on these distinctions. For instance, in the Mishnah (Mishnah, Pesachim 10:5), it is mentioned that at the conclusion of the Passover Seder, participants recite or sing the Hallelujah:

Therefore we are obligated to thank, praise, glorify, extol, exalt, honor, bless, revere, and laud [lekales] the One who performed for our forefathers and for us all these miracles: He took us out from slavery to freedom, from sorrow to joy, from mourning to a Festival, from darkness to a great light, and from enslavement to redemption. And we will say before Him: Halleluya. (Translation from seferia.org)

My new book showcases how the Hallelujah psalms in the Bible possess a unique characteristic. Seven of these psalms commence with two lines of equal syllabic length when employing two straightforward rules of Hebrew pronunciation. Psalm 150, in particular, adheres to a consistent meter structure featuring six similar elements and a seventh element distinct from the rest. This is in accordance with a prevalent pattern in the Bible of 6+1, as noted by the Bible scholar Umberto Cassuto (1883-1951).

It is conceivable that the melodious rendition of these two introductory lines in one of these six psalms or the entirety of Psalm 150 constituted the Hallelujah referred to in the Mishnah, sung or spoken during early Passover ceremonies and potentially at the conclusion of the Last Supper.

Additionally, the Mishnah’s description of the ancient Passover ceremony, particularly in the Kaufmann manuscript, may allude to such singing, as it states:

Therefore we are obligated to thank, praise, honor, glorify, exalt, and magnify the One who performed for our forefathers and for us all these miracles: He took us out from slavery to freedom. And we will say before Him: Halleluya. (Adapted from a translation from seferia.org)

The text above employs six verbs to articulate the praise of God, followed by a unique seventh element—an indirect address to God, who is not explicitly named but is defined by His deeds and miracles (“the One who did for us and our ancestors all those miracles…”). This recurring pattern of six similar elements followed by a distinct seventh element mirrors a structure found in certain biblical poetry, particularly in terms of meter.

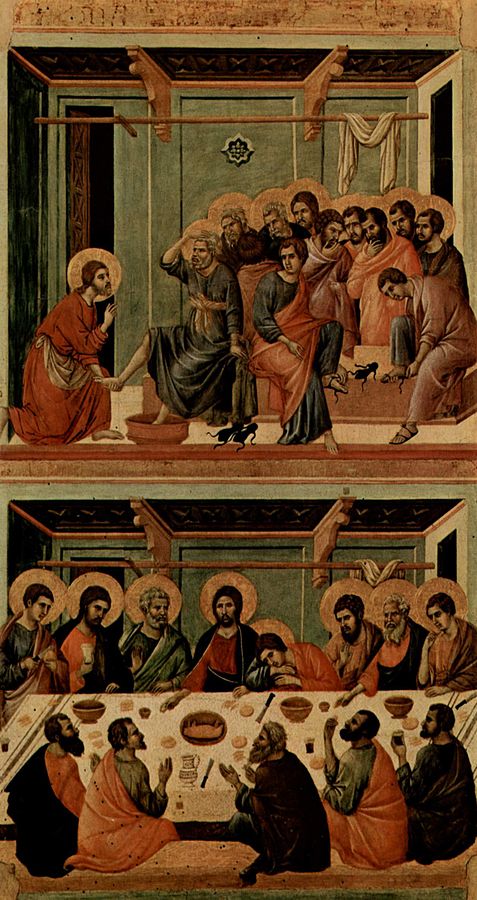

One could also entertain the possibility that the most renowned Passover meal and ceremony globally, namely the “Last Supper” involving Jesus and his disciples, included the rendition of a Hallelujah psalm in Hebrew.

In fact, the New Testament recounts that, following the culmination of the Passover ritual, specifically during the Last Supper, Jesus, accompanied by his twelve disciples, engaged in singing or reciting a “hymn” before departing for the Mount of Olives:

Matthew 26:29-30 states:

“λέγω δὲ [q]ὑμῖν, οὐ μὴ πίω ἀπ’ ἄρτι ἐκ τούτου τοῦ γενήματος τῆς ἀμπέλου ἕως τῆς ἡμέρας ἐκείνης ὅταν αὐτὸ πίνω μεθ’ ὑμῶν καινὸν ἐν τῇ βασιλείᾳ τοῦ πατρός μου.

καὶ ὑμνήσαντες ἐξῆλθον εἰς τὸ Ὄρος τῶν Ἐλαιῶν.” (SBL Greek New Testament)

And in the English translation:

“But I say unto you, I will not drink henceforth of this fruit of the vine, until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.

And when they had sung an hymn, they went out into the mount of Olives.” (KJV)

While the New Testament passage mentioned does not explicitly employ the Hebrew term “Hallelujah” to describe the singing at the conclusion of the Last Supper, it does utilize the Greek equivalent for “praise” in the word “hymn.” This strongly suggests a connection to Hallelujah. After all, a Hallelujah psalm is a form of praise dedicated to God, and the Mishnah records its recitation or singing at the end of the Passover Seder, a ceremony Jesus and his disciples partook in during the Last Supper.

Moreover, the fact that Jesus and his disciples sang or recited the “hymn” together potentially points to the possibility of metered two-line compositions, akin to the opening lines of most Hallelujah hymns. These lines were concise and easy to memorize, and their uniform and straightforward meter facilitated collective singing.

Further support for the association between the term “hymn” in Greek and Hallelujah hymns can be found in the Book of Chronicles (1 Chronicles 16:34-36), which contains an abbreviated Hallelujah hymn commencing with two identical lines. Towards the end, it is noted that the people responded with “Amen” and “Hallel,” a concept translated in the Vulgate as “hymnum Domino” or hymn to the Lord. It is plausible that the Vulgate translator intended to provide a direct translation of the word “Hallelujah,” which comprises singing praises or “Hallel” (hymnum) and “jah” (Domino).

However, it is worth noting that while the Vulgate uses in Chronicles “hymn,” the Septuagint (an ancient Greek translation of the Old Testament) does not incorporate the term “hymn.”

Although it is accurate to acknowledge that the absence of the word “Hallelujah” in the New Testament Gospels and the use of “hymn” instead leaves some room for uncertainty, the scenario where Jesus and his disciples sang or recited a (potentially metered) “Hallelujah” at the conclusion of the Last Supper remains highly plausible.